(I have kept this article in two separate parts although both parts are as important as each other in order to understand the full article. I would strongly suggest the reader reads Part One twice before moving on to Part Two. – Page 12)

PART ONE – A potted history.

Returning to the early 1970’s, only a few short years after the first shipment of Koi landed on our shores, it was soon discovered that the only places even mildly suitable for keeping them alive and growing them, was the traditional English garden pond.

There were many such ponds in the UK ranging from the magnificent stone courtyard and stately garden centrepieces designed by the likes of ‘Capability’ Brown and other famous garden architects of the day.

These garden architects promoted their own thoughts and beliefs that by incorporating water features into their creations, it would add yet another new dimension to their lavish designs.

At the other end of the scale there were the less lavish but far more attractive garden ponds built by private owners also to add more interest and sounds to their well-manicured gardens.

The sounds and sights of water features added an aura of peace, tranquillity and even a touch of ‘mystery’ for the casual viewer – especially when adorned with lilies, marginal plants, goldfish and even our native wild fish into these features.

In the early 1970’s the only magazine that brought any interest to a prospective or active Koi keeper bore the apt title of ‘The Aquarist and Pondkeeper’. I don’t deny how very impatient I could become until the very latest issue was finally delivered to my door.

I still recall how I’d skip rapidly through the boring aquarium sections until I finally got to the ‘Pondkeeper’ parts. Once there, I would read and re-read until the next issue arrived!

Reading about it was fine but it was not nearly as easy to see actual garden ponds and glean more information from the owners.

I didn’t know this at the time but there were only three specialist water garden outlets in the UK back then and thankfully they all advertised in the same magazine.

However, the doctrines they preached were identical to those preached by the magazine contributors and this left me in no doubt that their doctrines just had to be the gospel truth.

At the time, it made perfect sense to me that a perfect garden pond should be as close to ‘nature’ as possible. The experts of the day advocated shallow, saucer-shaped, in-ground indentations lined with plastic or rubber membrane that incorporated shallow areas for lilies and shallower borders to seat planting containers for the marginal plants. By adding ornamental fish and a waterfall or fountain, this would lead to a perfect replication of ‘nature’.

Of course, they advertised all these vital items in the magazine, and the magazine not wishing to turn away income welcomed them.

It cost me much wasted money and later a very lucky opportunity to be able to join the British Koi Keeper’s Society and to finally discover all these doctrines spouted by self-acclaimed experts were simply nothing more than a commercial scam.

We humans are simply incapable of duplicating nature; there’s only one man above capable of doing this and even he must wait for a decade or so to see his creation come to fruition.

It was about that time the few Koi enthusiasts around started to ask questions because despite how much they loved their colourful pets, ‘love’ alone did little to keep them alive.

The few who sold them in those times advocated they were true coldwater species. If that was the case why did they huddle up on the pond base and then turn on their sides when our winters struck?

It was a wise man that told us all to make our ponds deeper – not because the water would become any warmer, but the temperature on the deeper base would not be subject to the same temperature fluctuations a shallow pond base experiences. The ‘temperature fluctuations’ were far more dangerous than the temperature alone.

A one degree temperature increase or decrease to a human represents a four degree increase or decrease to a Koi.

Very soon after we also learned that pond plants in a man-made water-retaining structure did much more to damage the water make-up – rather than to simply appear to be ‘visibly natural’.

I can’t recall exactly when I first heard the term ‘pond filter’ mentioned – but it did seem to make some sense to me. After all, the term ‘pond filter’ must also mean ‘pond clarity’ and it would be nice to see our pets in crystal-clear water just for a change?

The popular filter for aquarium keepers back then was known as ‘the under gravel filter’ where a drilled plastic plate the size of the aquarium base was placed on the base and covered by a 1” layer of gravel. An air pump was connected to the plastic base that drew water downwards through the gravel and ‘air-lifted’ the water to the surface of the tank.

This was soon emulated by the keener Koi keepers of the day, by lifting out the pond liner and excavating a rectangular 12” deep, flat area, usually in the shallowest area of the pond, before replacing the liner.

Instead of a plastic plate, a network of 1.5” drainage pipes that led to a common manifold replaced this. The pipe had ¼” holes drilled straight through at random intervals (pure guesswork) and this network was buried under a 6” depth of washed pea gravel. A submersible water pump replaced the air pump and after connecting it to the manifold, this drew pond water down through the gravel bed and pumped the water back to the pond.

This seemed to be a perfect way of cleaning the water and also restoring good clarity, and it did just that!

Alas it only did ‘just that’ for a few months before the water pump started to slow down and then continued to slow down. Many water pumps burned out as a direct result of total mechanical blockage in the entire gravel bed. Immediately after this was detected it was a matter of great urgency to remove all the Koi from the pond before ‘grey water’ and severe anaerobic conditions followed.

Then came the need to take all the gravel out and clean it thoroughly before blasting the insides of the pipelines, replacing the gravel and starting the system up once more.

Later some well-meaning Koi person suggested the reason for this blockage could be because finer mechanical particles could be passing through the pump and back into the pond water. He suggested a swimming pool sand filter could be fitted after the pump and this would take in these fine particles and thus ‘polish’ the water?

It sounded logical to many of us as the thought of constantly cleaning bucket-loads of filthy gravel wasn’t the kind of ‘happy Koi keeping’ we’d expected.

The 18” model of the Lacron sand filter looked puny to most of us, and the 24” model didn’t exactly inspire confidence either. However the 30” diameter giant looked to be the perfect choice for the few dedicated Koi keepers around the country.

We bought them and fitted them only to discover our submersible pumps simply were not nearly man enough and only produced a trickle back to the pond. After a few disgruntled phone calls to Lacron, they told us the reason it was happening is that we also needed to replace our submersibles with their mighty external range of ITT Marlow pressure pumps!

Of course we all shelled out more loot and ordered these external monsters. Pretty soon we had perfect filtration for a few months where we congratulated each other warmly on our very wise choice of filters.

That was, until the first quarterly electricity bill landed!

(It was quite easy to wriggle out of that one for me by complaining bitterly to my wife as to the ridiculous high running cost of her latest clothes dryer.)

Alas running costs were not only the problems with our blue monsters, we soon discovered the only way they managed to produce crystal-clear water conditions in huge swimming pools was they needed high levels of chlorine (bleach) in the water to both trap the debris AND get it to waste by placing the multi-port valve into the backwash position first and then to waste.

Ah – so that was the reason our once 75 kilos of ‘fine’ granite sand had taken on the texture of concrete?

After discovering all this and more I put my 30” state-of-the-art Giant together with wonderful pump up for sale and persevered with the under gravel alone.

A reminder, I started keeping Koi in 1972 and I sold my sand filter in 1976, so all we crazy Koi enthusiasts could do was make our own filter systems because there were no ready-made units on sale anywhere.

In ’77, on my first visit to Japan I made myself a vow to take in all details of the filter systems used by the Japanese enthusiasts. Sadly all I saw were concrete chambers not stuffed with gravel but instead stuffed with large rocks. Furthermore, the owners of these filters hadn’t a clue as to how they operated because their landscape gardeners had built them and maintained them. I returned to England just as confused as ever.

Another thing to bear in mind was that membership of the BKKS came from both individuals who had previous backgrounds in keeping pet fish by way of aquarium experiences; whilst other individuals (like myself) had no interest in this and originally came into the hobby simply in order to make their gardens look much more interesting.

I think it must have been on my lone return trip from Japan in 1979 (discussed later) I first heard the terms pH, ammonia, nitrite and nitrate being bandied around in Koi circles by the former aquarium keepers.

Now, I must confess here, I had no idea what these scientific terms meant in relation to the Koi keeping hobby, and I even believed that the terms nitrite and nitrate were different spellings of the very same word.

Then I asked myself, if these terms were absolutely vital for us all to understand and apply; why then were these not mentioned by the water garden experts and outlets of the day, more than that – why was the subject of pond filters never even mentioned by these same experts?

After many hours of bending the ears of the owner of my local aquarium shop, I did finally get a feeble grasp of his lengthy explanations (from an Aquarist’s viewpoint) and duly bought all the necessary test kits from him.

By the way, I didn’t just buy them and bring them home, I insisted on a visit from him beforehand so I could watch him test my water.

Pretty soon I found myself flippantly telling other members that personally I could never have arrived at the stage I was, without relying on my test kits right from day one!

Well it seemed to impress some of them who later viewed me as an expert water chemist.

I really don’t know who was the first person in the UK to come up with ready-made pond filter systems but I do know it was a very close horse race between Malcolm Goodson and myself.

Malcolm advertised his units under the name of ‘Cyprio’ and his units were black polythene domestic header tank ‘seconds’ bought very cheaply from the manufacturers in all manner of sizes.

Malcolm simply drilled a 1” hole to connect the pond pump to the inlet of the box by way of a drainage specification tank connector (trust me, he’d have sealed it with Blu-Tac if he thought he could have got away with it)!

He’d either have the entry on some days under the gravel media supported by a cheap wooden frame and some perforated PVC sheet that made the water rise up through the gravel or on other days (depending on his particular mood) he’d have the entry at the top via a plastic spray bar (his proud invention) and let the water fall down through the gravel and exit by many perforations on the base of the unit.

Whilst it was always a welcome surprise for his customers, as to who would get the top or bottom feed versions, Malcolm had missed one minor design flaw.

You see Malcolm never considered what would happen if these units were left unattended for a long period of time as he never mentioned boring things like ‘maintenance procedures and intervals’.

And when the gravel finally blocked, trust me it blocked! Of course he never replied to the letters telling him the entire pond had been pumped onto their gardens that had resulted in one burned-out pump and an entire collection of Koi dead on the bottom of the now empty pond.

Malcolm had no time to deal with such petty matters because by then, he had cornered the entire UK pond filtration market and guess what?

The water garden centres of the UK that were increasing at a rate of knots were also stocking his Cyprio units on their shelves!

Of course, the units were a complete disaster and Malcolm knew this better than most. They later went on to become the most despised name by the Koi enthusiasts of the day and the derogatory term of ‘Black Boxes’ stuck. But this only produced extra sales from the newcomers, simply because they were ‘cheap and cheerful’ and also his newfound retailers could make a darned good profit margin from them!

I still know of NO other pond ‘filter system’ that can even approach the massive sales clocked up over the years by his Cyprio units. I do believe Malcolm’s ‘Coup de Grace’ followed around 1997 when he sold his entire ‘Cyprio’ business to Hozelock for a price said to be around £4,000,000.00!

Which confirms the old Yorkshire saying of ‘Where there’s muck – there’s brass’!

That done and settled, Malcolm upped sticks, moved to Spain, built a luxury mansion with a tennis court and still, as far as I know, plays every day.

Sadly, Waddy’s first two polypropylene super filters never had anything remotely like the same success of Malcolm’s boxes; although the better of the two did show the multi-chamber ‘rise and fall’ system for the very first time.

We are still in 1980 here, and as far as filtration was concerned, we in the UK were still completely in the dark ages. I made my second pilgrimage to Japan in 1979, determined to get to the bottom of the ‘filtration thing’ for once and for all.

The firm beliefs of the most avid UK enthusiasts in those days were that if our Japanese counterparts used anything at all in their endeavours, then it simply HAD to be of major importance to us over here.

I returned from that trip with sparse details and photos of pond drains, standpipes, discharge boxes, pond wall side feeds, concrete filter systems, ready-made Wakishimizu filter units, Biotron lamps to eradicate green water and Zeolite.

The ‘word’ from Japan was that we should dedicate one third of the system volume to the filtration and who were we to argue?

For starters I drew a scale model of a typical Japanese breeder’s concrete indoor pond system and had it published in the BKKS monthly magazine for all to see and marvel at.

Pretty soon the wealthier of the UK Koi enthusiasts began duplicating this system for their own systems.

Next I set about modifying the plastic grid plates used by the breeders as bottom drains in Japan, to also be able to cope with outdoor conditions.

My units had also to be adapted to allow installation on liner ponds – and the idea was to take the 4” lines to standpipes in a discharge box for daily discharge to waste.

That’s how my original ‘mushroom drains’ came to be, much more for my own use than anything else.

As fully expected, most of the UK experts who saw these units labelled me as being totally off my rocker and who also needed urgent medical assistance!

However, by 1981 I had much more important things to consider, namely designing and building the layout of my huge indoor Koi emporium soon to be known as ‘Infiltration Ltd’.

(My finest plans were mostly made on the back of fag packets whilst having rare tea breaks.)

The finished design was to have a large central pond to display all my most costly stocks and this would be surrounded by six ‘side ponds’ for cheaper stocks, together with a ‘staff only’ area for the treatment of damaged Koi.

Regarding the ‘side ponds’ they were a truly futuristic and well thought-out design in 1981, they must have also cost me a small fortune to complete.

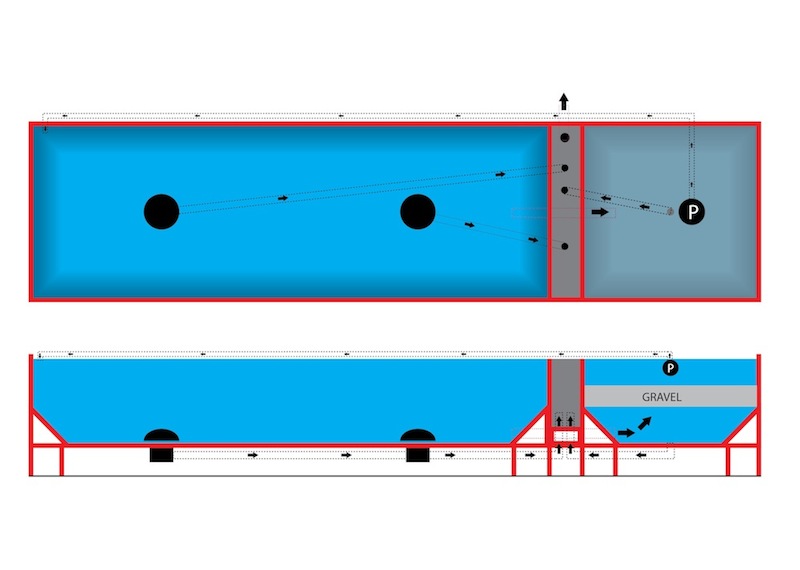

Andy, who takes care of my websites, has come up with my original design plans, which I think you may find to be interesting?

This design is by memory from 1981, but would still stand up today with a few modifications.

These six ‘side ponds and filters’ (28’ x 6’ x 4’ deep) were formed from 2” steel box section frames and lined throughout with 1” marine ply.

After this, box-weld liners were fitted to both pond and filter and held in place with a beautiful 6” wide, tailored, red wooden coping.

The 3” bottom drains, (outrageously revolutionary in those days), were connected to the grey PVC discharge box shown and stopped by 3” standpipes. The 3” drain from the filter was also connected to the grey PVC discharge box and an open 4” connection then emptied the discharge box to sewer by gravity.

A 4” open side feed connected the main pond to the filter and this could be stopped or opened by the push or pull of a Koi net handle should the need arise.

The only single mistake I made on these systems can be clearly shown on the section diagram where the incoming water from pond to filter tracks directly to the suction inlet of the submersible water pump!

Alas, it took me another 27 years to finally realise this!

On first fill, the drains seeped in drips on the floor and I still recall spending one bitterly cold Christmas Day of 1981 trying to address the problem by emptying the systems and re-sealing the drains with Paraflex – thankfully it worked!

Whilst all this was taking place a guy named George Hurst from south Manchester contacted me to ask if I’d care to pay him an urgent visit as he wished to show me something that may be of importance to me.

George, his wife and two sons were all avid Koi enthusiasts of the day and he was the only individual who had purchased one of my spare bottom drains.

I arrived there to find yet another Koi pond had been installed in his garden; Georges sons were not averse to rolling their sleeves up where Koi were concerned.

From memory it was a rectangular in-ground butyl pond of around 2,000? gallons, the pond base had my bottom drain installed centrally, with a large in-ground header tank outside the pond as the filter.

The filter contained pea gravel and there was a submersible pump placed centrally that took the filtered water back to the pond.

In short, a pond system design that was already widely used by others.

George pointed out to me that the system was running and asked me to watch when he turned off the pump. When the pump was switched off I noticed the water level rise in the filter box as expected when the pond is connected to the filter by a standard side feed. It did exactly the same in all sidewall connections?

George then pointed out to me that there was no sidewall feed from pond to filter and nor was there a standpipe and discharge box to take waste water to sewer – instead he’d simply connected the 4” bottom drain line directly to the filter and it was a single 2” ball valve fitted to the base of the filter that took the waste water directly to sewer.

At first it took a while for all this to register with me but soon it all seemed to fall into place and it did produce excitement and future possibilities as to what could be achieved by adopting George’s method.

The pond drain at the base of the pond would certainly be taking the majority of mechanical debris out of the pond and into the filter constantly, and this also applied to the ammonia-rich water.

In short, instead of the filter relying on a sidewall, mid water supply where most of the valuable bottom ammonia was discharged directly to waste via a standpipe, the filter was getting a constant supply of nutrients and waste 24 hours per day!

I remember driving home that day with a thousand thoughts running through my head but I don’t remember the journey – all I wished to do was to get home and find a note pad and a pencil.

In late 1982 after Infiltration had been fully open for business for six months, I introduced the first two ready-made filter systems ever fashioned from glass fibre. Both were multi-chamber ‘rise and fall’ units and both were available in 2,3 and four chambers. The cheaper units had 24” by 24” by 30” deep chambers that were simply connected to the standard pond wall feed with a 4” inlet and there were support trays included for the gravel media.

The more expensive units had chambers of five feet square by four feet deep, these included a discharge box that handled the 4” pond drains and also the 2” drains from each filter chamber. The discharge box had a 4” waste connection to be connected to the sewer.

Others immediately copied the cheaper units and derivatives of these are still available today, some later supplied them complete with Flo-Cor media rather than gravel.

In spring 1983 my second dry goods container arrived from Japan, it contained the first and only? Wakishimizu filter unit to come into the UK for testing purposes.

It also contained the first 25-kilo sacks of Zeolite stone ever to be seen in the UK as demand for this was high amongst enthusiasts.

Having spoken to the manufacturer regarding the Zeolite stone, the replies given did not exactly fill me with confidence. The claims were that it could absorb its own weight of ammonia before becoming fully charged, after this it was ineffective and would need cleaning.

I followed the advice given by the manufacturer to weigh and mark random pieces after they had first been soaked in fresh tap water for 24 hours. This done I placed a tray of it with the random pieces clearly marked in the first bio stage of the main pond filter.

I kept weighing these random pieces at monthly intervals and only after 10 months did I get a slight (5%) increase in weight. I had already given usage instructions by way of a leaflet attached to each sack that explained all this and the ways of re-charging the stones when required.

The re-charging could be done overnight by submerging the fully charged stone in a separate container with enough fresh water to cover it and then adding salt at the rate of one kilo per litre – as you may guess, this was impossible to dissolve!

Later I heard comments from others warning them never to allow salt into a pond that contained Zeolite as the salt would release the ammonia and poison all the Koi???

It’s quite amazing how some simple instructions can be twisted.

Moving on to the Wakishimizu unit, originally I set up a separate 10 ton Koi pond in the treatment area of the building and connected it to a side feed as instructed. It was a circular plastic upward-flow unit around 18” in diameter and around four feet tall. This was not a pressurised unit as were the larger ones, and simply had a lid that could be removed when required.

The manufacturer said there was two completely separate stages to these units, the first was the mechanical stage and the other was the biological stage.

On first inspection of the mechanical stage, the media was identical to the media contained in the bead filters of today, although I wasn’t to realise this until many years later.

The unit came with its own water pump, pressure gauge and various 2” control valves that were all fully automated. A simple perforated tray above and below this media prevented the beads escaping the box either into the biological stage or down into the waste lines.

When the pressure gauge indicated that the beads required cleaning, in stepped the automation. The water pump was switched off, a valve closed the return line, another opened the waste line and the water pump turned back on to backwash the beads. Once the pressure gauge indicated that the cleaning had been done, it automatically turned back to normal running.

In those days this was a rare delight to watch.

However, it was the biological stage that confused me the most. To describe it, this was a sheet cut to size of a clear plastic material that represented an open honeycomb when viewed from above and below. The depth of the material was around 9” and the plastic that formed the honeycomb was paper thin, of course it weighed hardly anything.

I couldn’t possibly grasp back then how water could be ‘filtered’ simply by passing it through a series of open holes?

The Wakishimizu ran well for a few months before the automation failed, but the high prices of these units, plus shipping costs would make these units very difficult to sell – yet another project abandoned.

In spring 1984 I discovered another biological media that also ‘filtered’ water through a series of open square spaces after Toshio Sakai finally informed me of his experiments with a material made to allow drainage of road surfaces when placed beneath these final surfaces.

He had formed the flat sheets into upward-flow cartridge blocks that were tailored to dimensions of his filter chambers and, after removing all the stones and gravel inside, he replaced them with these cartridge blocks.

In comparison to the heavy stone media these cartridge blocks were extremely lightweight and lasted indefinitely when submerged in water.

Toshio insisted that maximum performance of these open blocks could be achieved by adding heavy aeration below them.

I admit I had problems understanding his system, but after witnessing the water conditions these blocks produced on his ponds I had no hesitation in ordering a sea container to be filled with sheets of what I later christened as ‘Japanese Filter Mat’, various sizes of ‘Hi-Blow’ high-output air pumps and a new mechanical media being given rave reviews in Japan, namely the FOK filter brush.

These three items finally arrived for the first time in the UK in autumn 1984. Bearing in mind, no one in the UK had ever seen or heard of any of these items before (the only air pumps available were the ones used in aquaria) you can imagine how difficult it was for me to advertise, market and sell them.

Thankfully, at that time I had taken on the lease of an adjoining unit in order to increase my water space and the concrete block filters I designed were perfect for brushes, filter mat cartridges and heavy aeration below them.

In spring 1985, I invited others to come and see the water produced by the new systems. By pointing out the advantage of being able to finally ditch the gravel media of old (plus the laborious cleaning of it), these items gradually became in great demand by both the UK enthusiasts and the Koi dealers who seemed to be then springing up everywhere.

The lightweight media also allowed my ready-made units to be made more economically as they no longer needed to support the gravel beds with heavy wooden frames and perforated PVC sheets.

In late 1985 my very first Vortex Unit was delivered to Infiltration, it stood 75” tall and had a diameter of 54”.

Initially both enthusiasts and the Industry met it with roars of laughter, but within a few short months, every filter manufacturer in the UK started to produce their own cheaper mini-versions in order to get a share of the market.

My idea behind my original design was that a circular unit would be far more robust than a square one and by adding a ‘gentle flow’ of pond water into a large circular box by gravity, would produce the necessary centripetal action that would take mechanical solids down to the steeply coned base for removal by a 3” ball valve sitting at the very base of the cone.

It was easy to witness the collection and removal of the assorted debris just by looking. This was impossible to see in the smaller versions, as the ‘spin’ was FAR too fast.

I have no idea as to how many other ‘vortex units’ my original unit inspired manufacturers all over the world to produce them, and nor would I like to guess how many have been sold since then. But by the late 1980’s it was rare to see any Koi pond filter system without some version of a vortex unit.

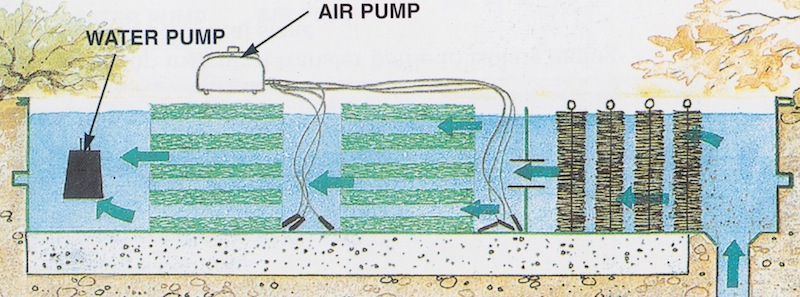

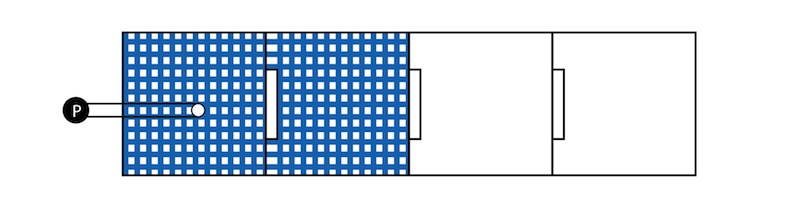

In spring 1986, by pure chance, I passed by some tailored upward-flow filter mat blocks awaiting collection and delivery by the carrier after they had been shrink-wrapped and addressed. These had been made to order for customers who had given us their specific sizes. Usually these were between 24” to 30” square with a depth of 9”, the particular one that caught my eye was an 18” cube.

I lifted the cube, looked at it and wondered if it would perform just as well by placing it on its side in a cheap tailored box that too held water with a width and depth of 18” and by subjecting the block (or blocks) to a horizontal flow of water rather than the standard upward-flow units?

At home later that night, out came the paper and pencil, and after an hour or so I had come up with the first ever horizontal-flow pond filter system!

I really had no idea if it would work, but if it did work I could produce this FAR more cheaply than my existing range of upward-flow units!

I must point out here and now that I didn’t look into the design as closely as I did my other units because the only thing that mattered to me back then was to make it as cheaply as possible.

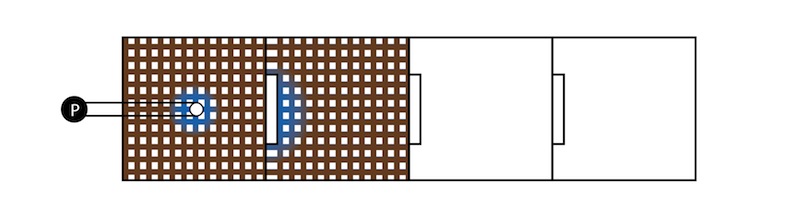

The prototype turned out to be an 18” wide x 20” deep x 108” long, simple, flat-bottomed box made from glass fibre, and to stop flexing there was a 3” x 3” timber frame glassed into the outside walls.

The running water depth was 18” and the two 4” sockets were in PVC.

The divider wall from the brush part into the bio part was a solid sheet with a 4” socket set in the middle and this only allowed me to drain half of the bio stage unless I wished take time to siphon the remainder out.

The central wall socket allowed me to insert a pipe stop in the socket to then allow the entire brush stage to be flushed to waste. Brushes were suspended on dowel rods and a few air stones provided the aeration between blocks.

I trialled the prototype at Infiltration before launching it under the name of ‘The Budget Filter’, which thankfully became the only design I’d made that no one else copied.

I can’t recall exactly how many units were sold between late ’86 and ’99 but I do know there wasn’t one single complaint from those who bought them.

But then, people only voice complaints if the product doesn’t do what it’s advertised to do?

Here’s an illustration of my very basic ‘Budget Filter’ system.

In 1995 I gave my Budget Filter system valuable page space in ‘Koi Kichi’, simply to let others know that these horizontal-flow designs were an ideal option for those who could make their own Budget Filter on a DIY basis.

I think it was the beginning of the ‘80’s when Koi started to take off in the USA and around the late ‘80’s when we first started to see enthusiasts from Germany, Holland and Belgium.

From late 1989 to 2000, the Koi hobby in the UK had more enthusiasts and Koi dealers than were ever even dreamed of in the early days.

Filtration wise in the UK, things stagnated from around 1989 to around 2000 apart from several new forms of biological media launched.

In this period we saw Andrew Worthington’s ‘Springflo’ media that was really just reels of plastic banding tape used to band parcels.

Another new media was a sintered-glass product name ‘Siporax’ used in aquarium applications but far too costly to filter large fishponds. (An alternative was found later for this free of charge as a waste product given off by the ovens around the Potteries area).

There was also plastic hair curlers said to be of use and also Alfa-Grog became popular with some enthusiasts.

The only other thing in that decade I considered to be of importance regarding ‘filtration’ was my firm belief that it was impossible to run multiple bottom drain lines into a common box and expect them all to enter the common box with equal flow rate.

In 1992, I designed my own Koi pond with this in mind and ran each of the four bottom drains into four individual filters each powered by an identical pump.

The first new filter came around 2001 when Nick Jackson announced ‘The Answer’ after I had put it through it’s paces for six weeks and was delighted with the results, I also christened it with the name.

This was a mechanical stage that surpassed all other mechanical stages of the day. A farmer named James Hosford, had invented the principle after finding a way of keeping his submersible pumps free from blockage when pumping slurry.

Nick Jackson, (later to launch his Koi accessory business to be known as Evolution Aqua), bought the rights for this, when used in fishpond applications, from James Hosford.

The Answer became the only ‘outside product’ I have ever endorsed, it truly was a remarkable invention.

Nick Jackson also had no doubts about the units and to endorse this, he sold all units with a five-year warranty.

I had seen many shower systems used on indoor ponds by several smaller breeders, some were ‘zig-zag trays’ where water passed down the sloping tray to fall into the next tray and so on. The Igarashi Koi farm near Nagaoka uses thousands of used drinks cans as media for his indoor shower system.

I can’t recall exactly when Mike Snaden of Yume Koi introduced the Micheo Maeda (Momotaro) stainless steel ‘Bakki Shower’ systems complete with Maeda’s ‘Bacteria House Media’ (BHM) to the UK but I think it may have been around 2000?

These have proved to be very popular with many enthusiasts and, as expected, many others have tried to copy them and use a cheaper form of media inside the showers.

(It has never ceased to amaze me that the parasites copying other filter systems never make more expensive and more efficient versions of the originals; instead they always produce cheaper and less efficient versions of the originals.)

I think it was around late 2002 when Evolution Aqua announced their new Nexus biological filtration system that was specifically designed to have their popular ‘Answer’ system incorporated as the mechanical stage.

The Nexus unit itself was a simple round upward-flow box, but the biological media inside was new to the UK, although it had been used on the Continent for some time before.

The media itself was invented in Norway and given the name ‘Kaldnes’, it is a semi-buoyant plastic media that Evolution Aqua were given sole distribution rights for use in fishponds and renamed it as ‘K1’.

The expensive advertising surrounding the Nexus units produced the desired results and it became very popular with many owners around the world.

Sadly, around 2003, ‘The Answer’ was discontinued due to the high cost of failed units being sent back for repair. These units employed many moving parts and the Oase pump driving them was only supplied with a two-year warranty, which meant Evolution Aqua had to supply replacement pumps at their own cost in order to honour their five-year warranty.

By removing ‘The Answer’ from the Nexus, all that remained was a circular plastic box. Initially circular sponges were supplied in an attempt to replace The Answer but unless they were washed out thoroughly on a daily basis they simply clogged and starved the biological stage.

Eventually static K1 inside a stainless-steel colander was employed to trap the mechanical debris, this became known as ‘The Eazy’ and was backwashed by air.

Still it was many times cheaper than the withdrawn Answer unit.

By 2003, Estrosieves used since 2001 as mechanical stages in Holland, were also introduced into the UK as a mechanical filter stage. Evolution Aqua made their own version of these under the name of Cetus and strangely recommended Nexus owners to buy this and install it before their Nexus units?

The mid 2000’s then saw hosts of other filter units known under the collective term of ‘Bead Filters’.

I’d rather say no more about these units as they look suspiciously – much like my sand filter that I sold way back in 1976!

I believe it was 2002, also at the Holland Koi show, I saw my first drum filter – but more on these later.

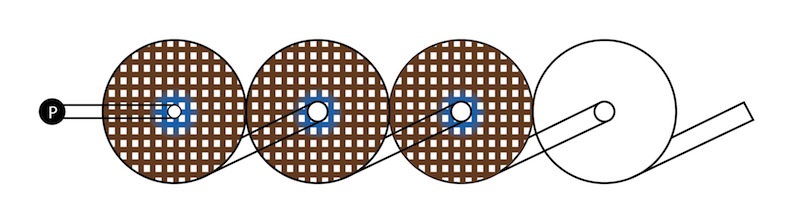

In order to summarise part one of this article properly. It was I, in 1981, who first designed and produced upward-flow boxes, either as single units or multi-chamber units. The reasons for doing so are that I firmly believed water levels rise equally by gravity and they do.

By placing a media barrier submerged half-way up these chambers, then this would ensure ALL water entering the chamber would give equal water supply to ALL media surfaces before exiting the chamber, thus ensuring that perfect biological filtration would take place.

My beliefs were also reinforced after personally watching many of these units filled for the very first time when watching the water rise equally through the media.

And I believed this to be the case for some 15 years or so before I had any serious doubts as to the validity of my firm beliefs.

From 1986 at Infiltration, all my filters consisted exclusively of upward-flow chambers with heavily aerated filter mat cartridges as the biological media. Each chamber had a 4” bottom drain to waste stopped by a 4” standpipe for daily discharge. Timber planks to serve as walkways for customers wishing to view the Koi in the ponds always covered these chambers.

When my pre-formed cartridge blocks were placed in the chambers, they were clearly visible to see this blue/green material with many open squares to allow upward-flow water to pass through unrestricted.

The planks were removed at 6-month intervals to check the boxes below. We removed the cartridge blocks to see if any debris that needed removal had built up below them.

I don’t know exactly how many times I took part in this servicing process but once the planks were removed it was almost impossible to see the blue/green filter cartridge below for a layer of thick, brown dust on the top of the material.

There was only one area where the blue/green material could be seen in all these chambers and that was exactly where the water left the chamber to go out and down into the bottom of the next one.

Of course it only took minutes to siphon the brown dust away to see the blue/green below as good as new, but six months later when the planks were removed it would always be there.

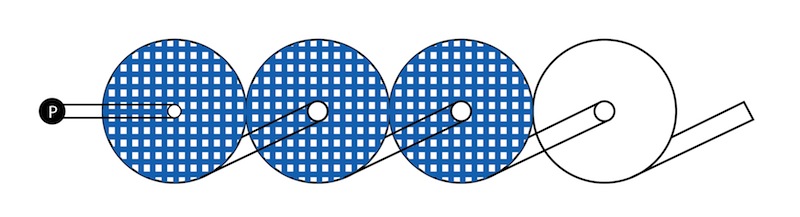

In 1991 I installed my new vortex system on the main pond with a prime vortex unit linked to three more identical units complete with circular 54” diameter upward-flow cartridge blocks. The water exited each chamber by way of a central 6” tube in the centre of the cartridge block. This unit was not covered by planks and could be viewed easily.

Over a few weeks, exactly the same dust started to appear to coat the surfaces of the cartridge blocks leaving only a central area surrounding the 6” outlet where the blue/green material could be seen?

I saw this happen so many times over the years, so why didn’t I pick up on it?

Why didn’t I finally realise that the only part of the filter media being serviced by the flow of water entering the chamber were the small areas where the blue/green material could be seen?

Dust driven up by the aeration does not settle in areas where there is water flow, but it DOES settle where there is none.

I have no idea why it took me so long to finally accept all my past beliefs were hopelessly flawed and I finally admitted this publicly in 2008.

In truth, I’d wasted 27 years of my life believing my very own fairy tale.

The trouble was, by then most of the Koi enthusiasts the world over were using upward-flow boxes and they didn’t exactly take kindly for this to be pointed out to them!

Of course this must also be applied to bead filters, as they too are upward-flow boxes – albeit pressurised.

PART TWO – What’s available today in 2013?

Most of the systems already mentioned are available today, from Nexus to Sieves to Beads, to Showers and various Multi-Chamber units.

Recent newcomers not already mentioned are Roto-Concept Gravity Shower units introduced in 2010, Bio-Qube bead units introduced in 2012 and my own range of Eric Units introduced in 2009.

As mentioned earlier, Drum Filters are increasing in popularity as mechanical units and are said to allow no mechanical particles to enter the biological stages.

So with all these systems on open offer to both experienced enthusiasts and newcomers; it’s not surprising that the final choices are ‘difficult’ to make.

I must point out that with the exception of my Multi-Chamber units originally designed in 1981, I have no actual hands-on experience with the other systems mentioned, but I do understand the principles behind them.

The first time I really had the opportunity to sit back and reflect in some depth on the Koi hobby from the outside was around 2008.

One of my major concerns was the fact I personally knew of many high-end enthusiasts who had entered the hobby with tremendous enthusiasm and also had no monetary restrictions.

These same enthusiasts built state of the art Koi ponds with the most expensive filters money could buy and then filled these systems with truly wonderful Koi to enter into the major Koi shows.

Then, after a short three years of experiencing the hobby, they threw in the towel and took up another hobby!

And the reason for this?

They had a wonderful collection of once valuable Go-Sanke and now the effects of hikui and shimi had rendered them to be almost worthless.

These problems have cost the worldwide Koi Industry fortunes over the years resulting from lost customers and lost business.

These problems have been around for many decades and yet there had only been one single attempt to rectify the situation by way of an Izeki product known as ‘Billion Liquid’ and that sadly resulted in failure.

I first highlighted these problems in my first book ‘Koi Kichi’ published in 1995 but had been asking many questions about these problems since 1982.

To explain to some readers what these problems are:-

‘Shimi’ is the Japanese word for ‘Freckle’ and these usually appear as small black spots that can ruin the appearance of Kohaku. Some can be removed completely by a deft flick of a trained thumbnail, whilst others falling on the scale-less head areas are almost impossible to remove without leaving tell-tale traces of where they once were.

‘Hikui’ is a far more sinister problem; it is a form of ‘skin cancer’ of the red (hi) pigmentation only. It initially appears as a small yellowish raised area on the red pigment and all attempts to remove it to date have resulted in bleeding of these areas, but when the bleeding is staunched the problem still remains and usually larger than when it was first identified.

Now whilst both these problems are definitely not transmittable from one Koi to the next and nor do they have any adverse effect on the health of the Koi displaying these problems; as far as showing these Koi at a Koi show is concerned, these are quite rightly viewed as ‘de-merits’ by the judges.

Popular opinion, from many quarters, suggests these are no more than ‘natural genetic disorders’ within Go-Sanke that we simply must accept as ‘bad luck’.

Whilst my own opinion is that calling on the word ‘genetics’ for assistance is simply a convenient cop-out and another golden opportunity to sweep the matter under the carpet once more and to forget about it all, as usual.

These problems have nothing whatsoever to do with genetics and here are just a few reasons as to why I can say this with some firm conviction.

· I have never witnessed either of these problems in systems less than 30 months old.

· I have seen these problems arising in enthusiast’s systems the world over, including Japan, for decades.

· I have seen these problems arising in systems with both hard and soft water.

· I have seen these problems affecting most bloodlines of Go-Sanke and from just about every breeder imaginable.

· I have never seen these problems arise with any Koi whilst still in the care of the Japanese breeders.

· For decades the very best Koi, owned by the most famous collectors in Japan, have been kept with the breeders to ensure that the owners ponds do not produce these problems.

· Many of the famous breeders will grow some of their tategoi for seven years and over before releasing them to the public and these Koi show no signs of either of these problems.

· I have personally purchased over 500 Koi from the Japanese breeders over many years for both my customers and myself, and kept them with the breeders to grow for three years and more. Not ONE of these Koi has ever shown signs of either of these problems whilst still kept with the breeders.

· My own filtration systems have been installed on ponds that once suffered badly with both these problems before my systems replaced the original ones. A few have been running on these ponds for well over 30 months now and, whilst the old traces still remain, not one single NEW outbreak has taken place.

· I have attended countless mud pond harvests for several decades, both standing in the water or at the edge of the water and have yet to see ANY Koi harvested with either of these problems.

· On every single occasion I have asked the breeders as to why enthusiasts have so many bad experiences with these problems, I’m told that it’s incorrect or insufficient maintenance of the filter system.

So why do the Japanese breeders have no problems with shimi and hikui with their concrete, filtered indoor systems that are very similar to ours?

Here are just a few reasons:-

· For starters, they discharge all pond and filter drains to waste via 4” standpipes every single day without fail.

· They have a permanent constant trickle of new water running into the system 24/7.

· After nine months of keeping their stocks in their indoor systems all Koi are moved into the field ponds to grow for three months in the summer temperatures.

· After the Koi are moved into the outdoor ponds, their indoor systems are shut down, emptied and then cleaned thoroughly and this includes the filter chambers and the media within.

· All these systems are then left empty to dry out for three months before filling up again in preparation for the autumn harvests.

· In truth, these systems are brand spanking new every nine months.

I’ll run another thought past the readers here –

If Koi can be kept showing neither of these problems, then surely this adds another new dimension to the water make-up?

And this new dimension must be of great added value to Koi of ALL qualities and ALL varieties?

I designed and manufactured my Eric filter units with these two huge problems firmly in mind and reasoned if the breeders could produce all this by cleaning out their systems every nine months, I needed a filter system that could do all this every single day.

Of course all other filter systems will eliminate the two big problems if they could be thoroughly cleaned-out every single day, it’s not unique to my systems, in truth it’s only basic common sense.

The problem here is that most of the other filter systems around today cannot practically be cleaned-out every day simply because it would take almost a day for some of the larger ones to be emptied, media removed, all chambers and all media cleaned, replace the media and then re-fill the unit before the pump can be re-started.

Not that I’m saying they MUST be cleaned out daily; once every two months would easily suffice, but it still means a whole day must be set aside for this. And when this realisation sets in, it’s no longer so attractive or exciting and simply becomes a chore.

I’ve mentioned this next part often before – but it may well be of importance to mention it once again.

The pond filter system is simply the ‘pond lavatory’, and once the pump starts up, the lavatory is in the ‘engaged position’ – and it will remain to be permanently engaged until the pump is stopped.

In truth, the pond filter/lavatory is in a constant state of gradual deterioration.

I have no idea who it was that actually suggested specified ‘time intervals’ as to when a filter requires cleaning or when it was suggested.

But it seems to me to be ‘the more often, the better’ – that’s if we don’t wish it to become full to the brim with unwanted matter that will certainly ‘taint’ the good water passing through and some of this will also be taken back into the Koi pond?

Returning to my filtration systems, these can be cleaned out thoroughly and re-started in less than three minutes, with no discernible loss of water and by just about anyone ranging from 10 years-old to 75 years-old and over.

If required they can be cleaned out twice a day when high temperature and high feeding rates are present and can also be cleaned out monthly when low temperatures and low feeding rates are applied.

They cannot possibly ‘block’, the running costs are extremely low and nor do they have any moving parts to consider.

I have often been accused of openly ‘slating’ other filter designs.

When I believe that explaining in great detail, to others, as to why they do have various shortcomings is perfectly good and valid information.

Or should I pretend I don’t know, and say nothing?

For instance, our rivers do not flow uphill – but they do give perfect and constant coverage of ALL the ‘static’ surfaces as they pass by horizontally.

If we really do wish the water in our filters to perform ‘party tricks’ then the very best way we can do this is to ‘pump it’ through an upward-flow box or upward-flow boxes.

The downside of this is, by making water do what it doesn’t want to do, will result in only a very small percentage of the static media surfaces within the box coming into constant contact with the water flow passing through.

Remove the static media surfaces and replace with moving media surfaces and this significantly reduces the chance of constant water contact with ANY of these surfaces.

Rivers can easily be controlled to pass through static areas of biological surfaces if ever that is required and, in my biological filters, it is required.

Rivers, from time to time, also fall downwards by way of waterfalls and man-made weirs/dams but falling water is not nearly so easy to control/harness with any real accuracy. Most of the real natural benefits of these in a river system are to greatly increase dissolved oxygen content.

————————————————————————–

There are Koi keeping terms and statements that have been bandied around for many years now, such as –

‘Stress’.

‘New Pond Syndrome’ (NPS).

‘The moment a Koi leaves the breeder, it starts to deteriorate’.

‘Spring Sickness’.

‘Aeromonas Alley’.

I don’t know who invented the first three terms but the last two were definitely invented by a person who wished to peddle a pond water conditioner.

The word ‘Stress’ is even a bigger cop-out than the word ‘Genetics’, ‘Stress’ can come to the rescue of just about anything we care to mention with our Koi.

One thing I’m sure of, I’ve yet to see a single Koi die because of ‘Stress’.

I’ve seen Koi jump out of a pond and die – that’s not ‘Stress’.

I’ve seen Koi die through an overdose of anti-parasite medications – that’s not ‘Stress’.

I’ve seen Koi die through toxic water conditions – that’s not ‘Stress’.

I’ve seen Koi die by flock spawning or parasites – that’s not ‘Stress’.

I’ve seen Koi die because of a lack of dissolved oxygen content – that’s not ‘Stress’.

Do you wish me to continue?

Koi don’t have to work in order to pay mortgages.

Koi don’t have to support and feed their families, nor do they need to buy clothes.

There’s no such thing as ‘Stress’ where Koi are concerned because there’s always a specific reason for Koi deaths or damages.

‘New Pond Syndrome’ (NPS) is a term often used when enthusiasts buy a new filter system.

The retailer and the enthusiast’s friends both warn the enthusiast that in order to ‘mature’ the new system, he and his Koi are sure to experience a period of living hell that can last six months or more before the filter finally decides to stabilise.

They also point out quite clearly that to get to this stage, without losing a few Koi in the process, should be accepted, as every enthusiast MUST go through this stage.

They also mention that many large water changes will have to be made in order to avoid toxic water poisoning.

I’m surprised that anyone would be stupid enough to take up the hobby after that kind of warning!

NPS does exist and can last up to six months, but only with some filter systems.

If the seller points out this warning before you buy the filter, I strongly suggest you look for another filter system that doesn’t carry the warning or phone another friend.

I’d also be VERY wary of those units with feed rate restrictions.

My filter systems are usually mature in around 20 days but the Koi in the pond never show any adverse effects at all and users have proved this on many occasions.

‘The moment a Koi leaves the breeder, it starts to deteriorate’ – Yes, this statement was often made and many resigned themselves to having to accept this as a fact.

And it will still continue to happen until the entire system responsible for this is improved and maintained correctly.

‘Spring Sickness’ and ‘Aeromonas Alley’ are one and the same nonsense terms intended to scare the living daylights out of Koi enthusiasts everywhere. As mentioned earlier, an individual who wished to offload his snake oil invented these terms.

He suggested that bacteria die away in winter (or go into hibernation) and when spring returns they are not in great enough numbers to populate our filter systems – but his expensive snake oil could do the trick in protecting the Koi whilst the bacteria had time to recover.

Of course, many did experience these problems in spring, and this only validated the truth of his statements with many others.

The bacteria does not die away and nor does it hibernate, because there’s always an ample supply of ammonia from the Koi by gill action alone.

However, bacteria do reduce in numbers when the ammonia supply reduces but this has nothing to do with water temperatures.

It simply means that the colonisation of bacteria on the few media surfaces in warmer times was so small it was already hanging onto a knife-edge.

The reduced amount of bacteria is now nowhere near strong enough to maintain this ‘knife-edge’ balance by supporting the reduced amount of bacteria. Thus the entire filter system ‘hibernates’ or ‘crashes’ and the entire pond water becomes anaerobic as a direct result.

This is not the fault of the reduced bacteria – it’s the fault of the filter system!

Enclosed recirculation systems, like our Koi ponds, rely completely on great filtration systems to constantly maintain the water quality.

In turn this allows all Koi in the water to thrive and produce their maximum potential irrespective of quality or variety.

A great filtration system produces much better water quality than any human can.

Incidentally, our filters systems must also be able to cope with our stocking rates.

Even the most lightly stocked recirculation system will need to cope with 30 times more than natural stocking rates.

For what we Koi keepers term as ‘normal stocking rates’ increase that end figure to over 100 times.

Ever wondered why natural parasites produce so many offspring in nature?

Ever wondered why very few fish die of parasitic problems in nature?

It’s because these parasites usually only have 24 hours after hatching to find a host (fish) to feed from, if they can’t do this they die of starvation.

If they hatch in even a moderately low stocked recirculation system, it becomes a luxury hotel for these chaps.

No filtration system in the world can prevent this.

I’ve mentioned before that no two Koi pond systems are exactly alike. For starters the source water make-up can vary dramatically, temperatures, feeding rates and stocking rates all play a part.

For those who wish to ‘change’ their source water make-up by adding chemicals, please remember that these chemicals will need to added constantly after daily water checks have been made first.

Carp (Koi) can adapt easily and continue to thrive in all manner of source water conditions such as high or low GH and KH and even brackish water.

As to growing them rapidly together with perfect body shape, this revolves around water temperatures, feeding rates and exercise currents.

In our individual recirculation systems, it’s important we learn to observe the behaviour of our individual collections as a whole, because the Koi will be the first to tell us if things are amiss.

I’ve used a method of checking if my Koi are in good condition or not for many years after a wise Japanese Koi breeder first pointed it out to me. By approaching the pond casually in a normal manner and watching the Koi for a minute or so, the Koi below should be swimming normally and some may be expecting food.

A rapid outstretch of an arm should immediately scatter healthy Koi in all directions and this indicates that they are alert. However if they don’t react to this sudden arm movement, it’s a good sign that something is amiss.

Periodic ‘flashing’ against the pond walls or base is to be expected from time to time as Carp often use this method to dislodge insect life from the algae.

‘Jumping out of the water’ however suggests there is a problem and Koi that become ‘loners’ and swim away from the rest of the shoal need attention.

Then is the time to take out the water test kits and the microscope.

Finally, if this very genuine article of mine comes over to the readers that it is simply another cheap advertisement for my filters, then it has failed miserably.

Peter Waddington, January 2013.